Jirga

Historically a people of unique characteristics, Pukhtoon societies, have held the concept of Jirga quite sacred to them and allowed this institution to rule them throughout their known histories. To a common person, Jirga is a body comprising of local elderly and influential in Pukhtoon communities who undertake dispute resolution, mostly through the process of arbitration. Compared to “Judicial System of the present day Governments”, Jirga ensures fast and cheap justice to the people. Indigenous to Pukhtoon tribal communities, Jirga is alive even in the areas now governed by Anglo-Saxon Legal system, used for petty interpersonal dispute resolution. The Jirga represents the essence of democracy in operation under which every individual has a direct say in shaping the course of things around him. Practiced this way, democracy operates as a spiritual and moral force instead of becoming an automation of votes,” The Jirga is a customary judicial institution in which cases are tried, rewards and punishments inflicted. From the outset, the use of the Jirga is limited not only to trials of major or minor crimes and civil disputes but it also assists in resolving conflicts and disputes between individuals, groups and tribes. This role may further be built-up to a developmental role of the Modern Jirga.

Jirga is an old custom with unmatched potentials for conflict resolution in the Pukhtoon belt of Pakistan and Afghanistan. It is a name given to the model, in which a Pukhtoon society operates, to undertake issues between individuals and between communities, to address concerns and look for solutions acceptable to all the parties having a stake.

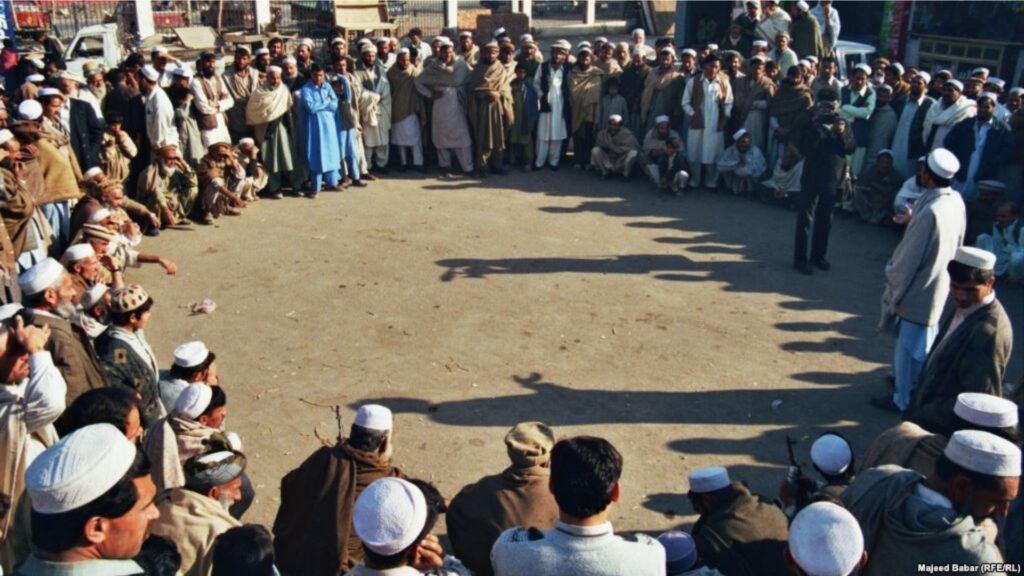

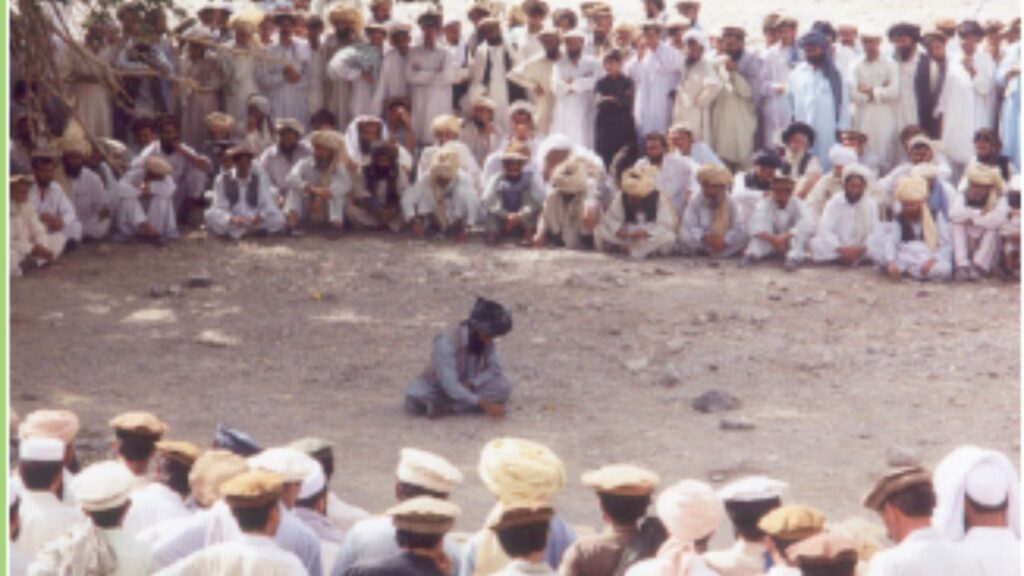

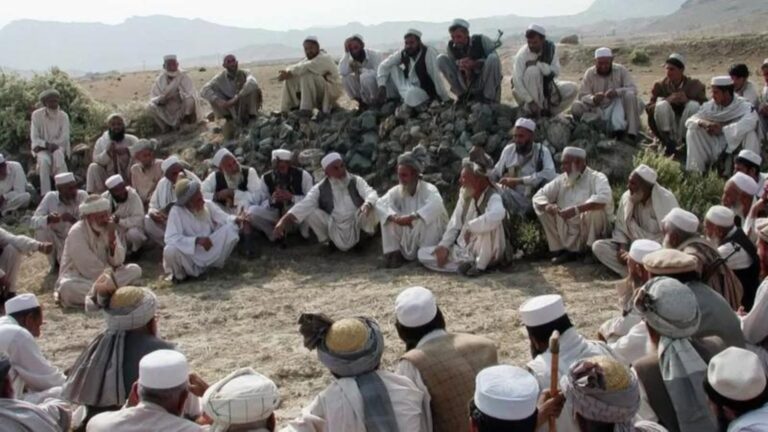

As a blue print of Pukhtoon life, Jirga is best summarized as a strategic exchange between two or more people to address an issue through verbal communication. The exchange may or may not result in an agreement on the issue, but the process itself leads the parties including the interveners to maintain a certain level of formal communication, thus ensuring peace. The system of Jirga is transmitted from generation to generation without any written protocols and written form of terms and conditions. This is considered a vital customary judicial institution where all are considered equal before the process. Mostly conflicts are resolved in an acceptable manner and everybody regards the results of the Jirga. However, some time use of enforcement of the decision is also required to bring justice. The Jirga is also considered jury because of its nature of composition and involvement. Jirga system ensures effective participation of the people in administering justice and makes sure that justice is manifestly done. Jirga also gives protection and security to the weaker from the aggressors. Jirga is called it is often a large meeting where participants gather in a circle All males of the locality are able to participate; men more active in public life tend to make their way to sit in the front row of the circle; those less concerned or vocal tend to sit or stand at the rear. A group who are recognized as unusually respected elders settled the final decision. In the Pukhtoon belt Jirgas are held in the Hujra, usually a building or part of a building that is a kind of community club in a village. Volunteerism is a core principle of the Jirga, though at its worst the institution is captured by powerful men who extract exploitative fees from disputants. The Jirga ideal, however, is of leaders who serve the community and are guests of God. So to spurn the decision of a Jirga is to risk the wrath of God. The spirituality of the Jirga is a mix of Islamic and tribal traditions. The Jirga shares much in common with the pre-Islamic Semitic restorative justice institution, the Sulha, which was practiced by Muslims, Jews and Christians in Palestine and across the Middle East Like restorative justice, the Jirga tradition is about solving a problem through the direct participation of parties on different sides of a crime or conflict and then restoring relationships among those parties through reparations and reconciliation. Forgiveness has a more central role, the expectation to forgive is much stronger, in Jirgas than in western restorative justice. During our 2013 fieldwork more than one person said ‘You Westerners believe in forgive but don’t forget, we believe in forgive and forget’. When fifteen different Muslahathi Committee members and disputants from different locales were asked, ‘How often do the victims forgive offenders who have committed serious crimes like murder’, answers ranged from ‘the majority of cases’ to ‘always’, with most saying 80 or 90 per cent of cases. Jirga justice is usually speedy. Most cases are settled in a few days. One option for parties in conflict is for the Jirga members to take waaq (power of decision making) from both sides to make a decision. Once waaq is taken, the decision made by the Jirga according to custom is binding. The parties have no right to refuse the decision of the Jirga in traditional law after waaq, though state law gives them that right. In traditional law, disputants have the right to refuse to give waaq. Then they are given the option in FATA and some other Pukhtoon tribal areas of whether they want the case to be decided according to Sharia law or Pukhtoonwali (customary tribal law). Or they can forget the Jirga if they want and go to the state’s courts instead. Or for more minor issues (but not serious ones like murder) they can opt for Maraka. With Maraka, parties to a conflict select one or two representatives from both sides to resolve an issue ‘according to the prevailing traditions and needs of the families’ caught up in the conflict (Gohar 2012: 55). Within the Jirga process, disputants are empowered to say that they have lost confidence in the Jirga members as fair or honest or competent. There is an obligation to respond to this by adding new members to the Jirga of the choosing of both sides of the dispute to break the roadblock. So the Jirga is a more deeply legally pluralist institution than restorative justice or state justice in other parts of the globe. There are many layers to this pluralism. First the parties are asked who they wish to be the decision making 6 members of the Jirga and agree on a composition with the other side. Later they can change this view and add new members. They decide whether their Jirga will be binding or whether they can walk away and ask for another Jirga later. Then they can opt for Sharia Law or customary law (which most do because they do not fully understand Sharia law). Or they can opt for the police station reconciliation committees, or the courts.